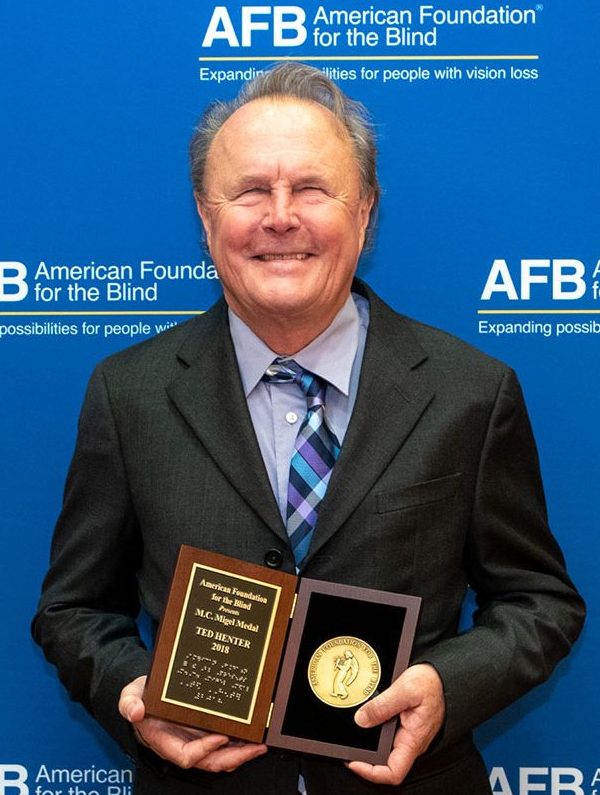

Photo: American Foundation for the Blind

Ted Henter (BSME ’74) remembers swerving as the lights came toward him.

Those lights would be one of the last things he’d ever see.

After two unsuccessful eye surgeries, Henter, then 27, awoke with a face full of stitches and a permanent disability.

But Henter said he spent only about 10 minutes lamenting the loss of his eyesight before a calm washed over him. “I started feeling like, ‘Well, this isn’t going to be so bad. I’ve just got to figure out how to deal with it,’” he said.

Almost 40 years later, Henter was named the 2018 recipient of the prestigious Migel Medal by the American Foundation for the Blind, joining the likes of Helen Keller and Sen. Tom Harkin as fellow recipients. Henter was awarded for the development of Job Access With Speech, or JAWs, the groundbreaking computer screen-reader program for the visually impaired.

“At the American Foundation for the Blind, we have a motto of life without limits, and Ted really embodies that,” says George Abbott, chief knowledge advancement officer at the American Foundation for the Blind. “He lost his vision as a young adult and he didn’t let that stand in his way.”

80 stitches and a new reality

Henter has been figuring things out his entire life.

“When I was in the fourth grade, I took apart a coaster brake on my bicycle and my dad was amazed I could put it back together,” he says. When he got a motorcycle at 15, he promptly took it apart. “I wanted to see how things actually worked,” he says.

Speed and function defined his young life. Growing up in the Panama Canal Zone, Henter was extremely active. He learned to water ski at age 5 and later took up surfing. When he was older, he began racing motorcycles.

He received his bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from UF in 1974, initially planning to design race cars, but he decided to pursue motorcycle racing full-time.

After placing eighth in the Venezuela Grand Prix in 1978, he traveled to England to prepare for the Spanish Grand Prix. Leaving the racetrack one night in a rented Chevrolet Chevette, Henter forgot to drive on the left side of the road.

“I was just daydreaming, making plans for my trip to Spain when I saw the car coming,” Henter says.

In the last three seconds, Henter instinctively swerved right as the other driver swerved left and the two collided nearly head-on. Henter, not wearing a seatbelt, broke the windshield with his face. He woke up with 80 stitches and a new reality: He was blind. The other passengers, wearing seatbelts, suffered only minor cuts and bruises.

Henter says it took him about three years to become comfortable with his blindness and to fully regain his self-esteem.

Learning to adapt to his blindness “was all very motivating,” he says. “Necessity is the mother of invention and I had a lot of necessities.”

A powerful advance

The main necessity? Landing a job.

Returning to the United States, Henter consulted with the Division of Blind Services and learned that the field of computer programming was opening up for the blind. He enrolled in computer programming classes at the University of South Florida and was introduced to some developers of talking computers from Maryland.

In 1981, he moved with his wife Mel and six-month-old daughter to work for Maryland Computer Services.

“I was really into making computers accessible for blind people,” Henter says. “That was my specialty.”

After familiarizing himself with the software that made talking computers possible, Henter traveled around the country training people on how to use them. Through these trainings, Henter met his future business partner, Bill Joyce, who was also blind and partially deaf.

There was a problem, though. The screen-reader software was getting stuck with the old technology, running on MS-DOS as the whole world was moving toward the graphical user interface technology led by industry giants such as Microsoft and Apple. The blind and visually impaired community was getting left behind.

In 1987, Henter-Joyce was founded in St. Petersburg, Fla., with Henter at the helm as the principal developer on a new piece of software that would bring the blind community into the digital age.

JAWS became the most influential and powerful software for the blind or visually impaired, allowing them to utilize computers in school, at home or in the workplace.

“He really brought to the market a very robust tool that gave blind people an opportunity to have a whole lot of freedom and access,” says Abbot, who uses JAWS every day.

Over time, Henter-Joyce grew to around 70 employees, almost half of them blind. Henter says that building a company that employed the blind was important for philosophical reasons, but also practical ones. “We were familiar with the issues, with the bugs and with what a lot of users would want to see in improvements,” he says.

“Just get up and do it”

Photo courtesy of Ted Henter

Henter has also maintained his thrill-seeking, adrenaline-fueled passion for life, taking part in water skiing, snow skiing and kayaking. In water skiing, he won the 1991 World Championship for Disabled Skiers and won six times on a national level.

“To get up and water ski when you can’t see, you have to have faith in the driver and be careful,” Henter says. “But you know, you just have to get up and do it.”

For Henter, it’s all about enjoying what you love.

“Sighted people think, ‘Oh that’d be terrible to be blind,’ but really, you get over it,” Henter says. And he insists he is not endowed with supernatural levels of optimism. “I have a lot of blind friends who are just as successful and as accomplished and as happy as I am,” he says.

Now in his retirement, he and Mel split their time between the Panama Canal Zone and St. Petersburg. They volunteer with the Helen Keller School for the Blind in the Republic of Panama, raising money, buying resources and even building a computer lab.

“Mel and I have been very successful in our personal lives,” Henter says, “and we’ve been able to spend time and money helping other people. So life’s been good.”