A long road to freedom and opportunity yields an indestructible legacy for future generations of UF engineers

This story was originally posted on the Department of Materials Science & Engineering website.

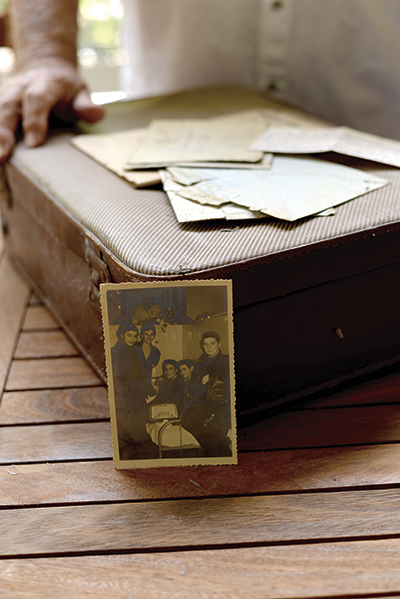

On the tropical patio of his Longwood, Florida, home nestled against the Wekiva River, Ben Botic pulls out a small dusty suitcase and unpacks a tattered trove of adventure, risk and dogged persistence. “These are friends from my Serbian community,” he gestures, holding up a weathered silver gelatin memento that dimly reflects a half-century old memory. He unfolds a creased work permit, then thumbs proudly through a yellowed graphic notebook of formulas — a chronicle of intellectual rigor and encounters that changed his stars.

Ben (MS MSE ’71) and Hella Botic

Now a nearly retired president of Suncraft Engineering & Construction, Branimir “Ben” Botic (MS MSE ’71) navigates the downramp of his career by enjoying the hard-won fruits of his American life —literally, sharing the valuable bottles that occupy his two refrigerated wine cellars — and by sharing his passion for educational opportunity as he would uncorking one of his vintage Bordeaux-region cabernets.

“There’s no substitute for experience,” Botic says. “I liked the idea of supporting engineering students by providing access to things that give them an advantage after college. For those who want that and have the work ethic, I don’t want them to be constrained by a lack of means.”

More than most, this political refugee from the former Yugoslavia (now Serbia) understands both the need and the value of the convergence of hard work and unexpected opportunity. Along with Hella, his wife of 54 years, son, Bryan (UF BS Building Construction ’93) and daughter, Michelle Botic Hughes (UF BS Business Administration ’92), Ben established the Botic Family Scholars Professional Pathways Fund, which provides experiential learning opportunities for undergraduate and graduate students in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering (MSE).

Growing up in the totalitarian regime of 1950s Yugoslavia, Botic didn’t have the connections needed to attend college. His father was killed by the government, and they refused to allow the 16-year-old Ben to leave the country to join his uncle who had emigrated to the United States. When his mother heard that one of their neighbors was going to flee the country, she told Ben to go with him.

“It took us five days to get across the border,” Botic says. “We took a train, then walked through a very arid, desolate area. I was eating raspberries and licking leaves in the morning dew for hydration. When we got to Italy, we were captured by Italian police. They jailed us, then put us into a camp, waiting to be returned to Yugoslavia. They didn’t watch us very closely in the open courtyard, and there was a building there with a second-floor room that had old iron bars on the window, where we jumped out. We escaped, got on a train in Genoa, then hopped a bus in Sanremo, Italy.”

“It took us five days to get across the border,” Botic says. “We took a train, then walked through a very arid, desolate area. I was eating raspberries and licking leaves in the morning dew for hydration. When we got to Italy, we were captured by Italian police. They jailed us, then put us into a camp, waiting to be returned to Yugoslavia. They didn’t watch us very closely in the open courtyard, and there was a building there with a second-floor room that had old iron bars on the window, where we jumped out. We escaped, got on a train in Genoa, then hopped a bus in Sanremo, Italy.”

Across the border in Nice, France, Botic worked construction in the French Riviera, then followed the tourists back to Paris when summer ended. He found a church boarding house for kids his age and took on more construction jobs while learning French at Alliance Francais, a Sorbonne school that offered classes for non-French speakers. Ben was the only student among his fellow immigrants to finish the required courses.

At 18, Botic boarded the Queen Mary to New York, finally reuniting with his family, including his uncle in Detroit who ran a bakery. Speaking no English, Ben enrolled in a grade school with much younger classmates near his uncle’s home to learn the fundamentals of the language.

“The teacher, Mrs. Carr, saw something in me, and she insisted that I go to high school,” Botic says. “There was a city technological high school that accepted exceptional students who were commended by their teachers. They struggled with which grade level to place me. I was getting ‘A’s in Algebra, Physics, Chemistry and Electrical; not so good in English.”

Botic earned both his diploma and a license to do electrical wiring work. Rather than ply his newly minted trade, he set his sights on a college education at the University of Michigan where many of his friends enrolled. Ben found an empathetic counselor who agreed to admit him on the condition that he sharpen his schoolwork — particularly in English — with a couple years at Henry Ford Community College.

“When I went through the line to sign up, they noticed that I lived in Detroit, not Dearborn,” Botic says. “But Henry Ford CC only admitted employees of the Ford Motor Company or residents of Dearborn. I asked a friend, ‘You live in Dearborn, right?’ He allowed me to list his Dearborn address, and we certified it at the police station. I just had to make sure I didn’t go back to the same person to enroll.”

There he excelled in the sciences and took on extra tutors to hone his English, giving Botic the opportunity to transfer to Michigan. Overcoming the naysayers who predicted his unlikely graduation, he finished on the Dean’s List while working at a foundry doing x-rays and scans to inspect stainless steel parts for the aerospace industry.

His exemplary work in the lab won over a professor who wanted him as a research assistant in the Ph.D. program, but fate intervened. After being drafted for service in Vietnam, then being granted 4F status due to a childhood injury, Botic traveled to Orlando, Florida, to visit defense contractor Martin Marietta (now Lockheed Martin) with his roommate, who hoped to secure an employment deferment. Though Botic was settled on graduate school, he joined his roommate for the interviews, then the two went fishing in the Keys over the weekend while Martin Marietta deliberated offers.

“When we came back, they offered me a job,” Botic recalls. “I wasn’t even looking for one! And I’m getting married in a few weeks and am already registered for graduate school at the University of Michigan.” Lockheed countered by offering to pay for Ben’s graduate degree at the University of Florida, where he studied under Professor Frederick Rhines, founder of UF’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering, and father to Walden “Wally” Rhines, Ben’s classmate at the University of Michigan. With the prospect of escaping the bone-chilling cold of Michigan sealing the deal for Hella, all the boxes were checked.

As one of the youngest managers at Lockheed, Botic received a cryptographic clearance — the highest available in government contracting — and applied his expertise in microscopy and single-crystal structures to help provide the military’s “Star Wars” program indestructible electronics shelters that would survive nuclear attack. It was an ideal based in his materials science training that later found expression when Botic was building his Florida homes. Unable to find workmanship equal to his standards, he returned to school for one year to obtain his construction license and began applying his research know-how to creating durable custom homes in the hurricane-battered corridor of Central Florida.

“When we got hit with four hurricanes in 2004, I only received two phone calls from my customers,” Botic says. “Both were to tell me that their neighbors evacuated to the houses I built for them because everyone else’s homes had damage and leaks.”

His construction venture, Suncraft — now a full-service design, development and general contracting firm that he runs with son, Bryan — boasts several Parade of Homes awards, and derives most of its business from repeat customers and referrals. It’s a testament to a recipe for success Botic illustrates by extracting a chilled German Riesling from his beloved wine cellar.

“You must be intentional about the details,” he explains, assuming his favorite role of host-sommelier. “Here’s a cold bottle of wine and a warm glass. I tip the glass slightly, pour a small amount and slowly fill it. If I immediately fill it up, half of it will end up overflowing on the floor. Many of my friends in Florida live in houses I’ve built. I had better pay attention to detail and make sure I give them my best work. My goal is to make sure I make their dreams come true.”

Much to the delight of the Botic Family, their philanthropic support of MSE students at the University of Florida is accomplishing just that, inspired by the unforeseen opportunities seized upon by their determined patriarch.

Ben Botic’s Keys to Success

- You must believe in yourself! Failing that, you’ll never succeed. I remind people that ‘God created only ONE you.’ Don’t put yourself in a box defined by race, nationality or class. Each human being is unique, and they offer the world something no one else can.

- Education is paramount. My life would be completely different without it. The more educated we are, the better we are as a country, a people and as a world. You’re not born with knowledge; it’s acquired. When I first got to Detroit, no one would give me a chance. But I advanced because I persisted and attended classes.

- Use your critical thinking skills. I would ask my employees why they did a certain thing a particular way. If their answer was ‘I don’t know why,’ I couldn’t use them. Be intentional about everything you do.

- At some point, we all need compassion and tolerance. It is something in short supply right now. I think about all the people who helped me along the way. There are going to be people in your life whose paths can be completely changed for the better by a small act of kindness.