Dr. Damon Woodard joined the faculty of the Herbert Wertheim College of Engineering in 2015 and now serves as director of UF’s Biometrics and Machine Learning Group, among other duties.

This story was originally published in the Winter 2022 edition of Florida GATOR Magazine.

High school dropout. Abusive home. Poverty. The odds were against Damon Woodard. But propelled by a fierce inner drive and a few supportive souls along the way, he would go on to become one of the nation’s leading experts in biometrics and machine learning.

Story by Barbara Drake (MFA ’04)

Portrait by Aaron Daye

THERE’S MORE TO BIOMETRICS EXPERT Dr. Damon Woodard than meets the eye — or the “periocular region,” as his research specialty is known. An associate professor in UF’s Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Woodard is a pioneer in digitally identifying people through the features around the eye – eyebrows, wrinkles and skin folds — even if the subject is masked or the image is blurry.

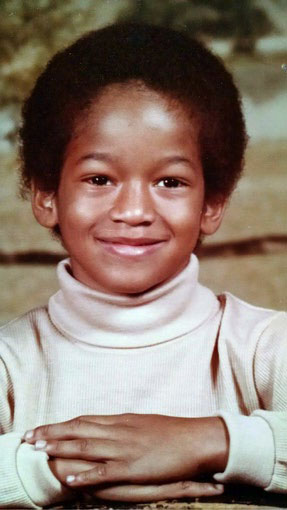

Damon Woodard in the second grade, in New Orleans. As a

child, he was quiet, determined and focused, he says.

“As I joke with my students, it’s not like the bad guys want to pose for the camera, so in biometrics, you have to use what you have,” Woodard said in a recent interview.

Solving real-world problems is Woodard’s passion, and since 2007, his efforts have been rewarded with $20 million in research funding from the intelligence community, the Department of Defense, the National Science Foundation and other sources. UF tapped his problem-solving bent in 2020 when he was named Director of AI Partnerships for the university’s Artificial Intelligence Initiative. In that role, he reaches out in multiple directions, like Spiderman’s “Doctor Octopus,” to arrange AI collaborations and trainings with industry, government, nonprofits, K-12 schools and universities around the state.

It’s a role that calls for well-honed people skills, not a characteristic typically associated with engineering wizzes.

But Woodard is not your typical engineer or academic.

Three decades ago, he was a high school dropout “just running the streets” of New Orleans, he said. How he rose from those bleak circumstances to become the first African American to earn a Ph.D. in computer engineering from Notre Dame is a testament to the people who believed in him — and to the inner fire that refused to go out.

“I’m the type of person who, when you tell me I can’t do something, that fuels me even more to succeed,” said Woodard. “You are not going to outwork me in terms of effort, and I am not going to quit.”

From Streets to Mechanic School

Woodard grew up in the Crescent City, one of five sons born to a homemaker and a pipefitter for the Navy shipyard. The family lived in a two-bedroom home, and “money was tight,” Woodard said, noting that anger and physical abuse permeated the household. But his mother, Gwendolyn Woodard, always kept an eye on her boys’ comings and goings, and urged them to aim high with their studies.

By the time Damon was in high school, his father’s volatility had grown more heated.

“It was hard to concentrate on doing homework and being a student in that environment,” he said. “It was just too much.”

At age 15, he dropped out of school and hid it from his mother for a year.

“I pretended I went to school, and I was just running the streets,” he said.

When he finally revealed the truth, Gwendolyn had been working outside the home for a while, holding down several low wage jobs to make ends meet. Damon’s news came as a shock.

“I know that really hurt her,” said Woodard. “But I told her I would go back to school. I always knew I would. I even had a plan.”

At age 17, he enrolled in trade school to become an auto mechanic, a skill he planned to use to put himself through college. Simultaneously, he studied to earn his high school

equivalency diploma.

“I studied on the way to the trade school, on the bus,” said Woodard. “I studied at the bus stop. I mean, I carried my books everywhere with me.”

In 1990, shortly before he turned 18, he earned his GED, and Gwendolyn — who by then was no longer living with Woodard’s father — backed her son’s college dreams, even if she had no money to spare for tuition or books.

“My mom said, ‘We’ll figure it out. We’ll make it happen,’” he remembered.

“I would work during the day as a mechanic, come home, take a shower, eat really quickly, and then change clothes and go to school at night.”

Damon Woodard on how he put himself through night school at Tulane University

Night-School Naysayers

In 2005, Damon Woodard became the first African American to receive a doctorate in computer engineering from Notre Dame. He is shown here at that momentous event with his dissertation adviser and mentor, Dr. Patrick Flynn. “He taught me a lot during my time as a graduate student,” says Woodard, “and all these years later, I find value in his advice as a faculty member.”

Woodard applied to Tulane University and in 1992 was accepted into its night program for computer information systems.

“I would work during the day as a mechanic, come home, take a shower, eat really quickly, and then change clothes and go to school at night,” remembered Woodard.

One evening in class, a guest speaker who taught C programming shared that he had a doctorate. Intrigued, Woodard asked if that was the highest degree a person could get, and the speaker told him yes. Later, when the speaker asked the class to share their individual career plans, Woodard confidently announced he was going to earn a doctorate, too, prompting whoops of laughter from his classmates.

“They started laughing because, understand … the general outlook then was that night school students couldn’t hack it in day school with the regular students,” said Woodard.

“That was almost thirty years ago, but I remember it like yesterday,” he added. “It became one of the main things that drove me.”

Woodard’s strong work ethic and stellar GPA spurred a staff member at Tulane’s computer lab to recommend he transfer to the regular program for computer science, a much harder course of study. The staffer introduced Woodard to the chair of the engineering department, who recognized his potential.

“She was really nice and offered me a partial scholarship,” remembered Woodard. “She said, ‘OK, let’s see what you can do; you’re going into both engineering school and day school now, so it’s a different ballgame.’”

As any former engineering student can tell you, the first two years of school are filled with demanding courses such as Calculus I, II and III, Differential Equations and Statistics.

“‘The widow-makers,’ ‘the murderers,’ we call them,” joked Woodard. “For me, I didn’t have the math foundation to tackle those courses. It’s one thing to get a GED, but it’s completely different to operate at that [higher] level.”

Worried he would fail, he turned to his mother. She told him to buck up and get a tutor, which he did.

“I’m not going to lie; it was a fight,” he admitted. “That tutor taught me four years of high school math in a little over six months.”

Woodard’s dream at the time was to become “the Black Bill Gates,” he said, and it pushed him to excel. In his senior year, he received the Highest Senior GPA Award from the National Society of Black Engineers in 1997 and earned a bachelor’s degree in computer science and computer information systems.

Finding His Academic Home

Advice from an African American Ph.D. student at Tulane turned Woodard’s thoughts from entrepreneurship to graduate school, especially when he learned that in 1994 there were fewer than 100 Black PhDs in computer science.

“I said, ‘I am going to be in that number. I’m going to do it.’ It was my new goal,” said Woodard.

Buoyed by support from the Graduate Education for Minorities (GEM) Fellowship Program, he chose Penn State University to earn his master’s degree in computer science and engineering.

The program was good, but in the late 1990s the atmosphere on campus toward underrepresented students was “extremely hostile” there, he said.

On his first day, he entered his graduate computer architecture class. He was the only Black student in the room.

“I’ll never forget it,” said Woodard. “A [white] student comes up to me and say, ‘Are you sure you’re in the right class? Because this is Advanced Architecture.’”

“Growing up, I had experienced every sort of micro/macro aggression you can think of, so I had a tough skin, but this was through the roof,” he said. “And you should have heard the stories the other African American graduate students used to tell in the dining hall.”

In 1999, Notre Dame flew Woodard to Indiana to check out its Ph.D. program in computer science and engineering. The university was home to the GEM program headquarters, and after just 15 minutes on the smaller, more welcoming, campus, he knew he had found his academic home.

Building a Life Amid a Death

While Woodard was working toward his Ph.D., 9/11 happened. He immediately wanted to drop out of school and join the Marines to fight al-Qaeda, and confessed as much to a trusted professor.

“I was young, and I wanted to drive tanks,” said Woodard. “But the professor told me, ‘Don’t do it. Your talents can help your country in a different way.’”

The other way was through biometrics research, the specialty of new faculty member Dr. Patrick Flynn, who would become Woodard’s dissertation advisor. While the field of biometrics had existed for decades, the 9/11 attacks spearheaded a global push for countries to “develop and implement systems to collect biometric data” to accurately identify terrorists, as a UN Security Council resolution stated.

After all, in the run-up to 9/11, al-Qaeda was able to exploit weaknesses in border screening to send 19 operatives into the United States undetected. More advanced biometrics tools were urgently needed.

Enter Damon Woodard. And enter his new research partner: the U.S. government.

In August 2005, Hurricane Katrina destroyed Woodard’s family home and all their photos.

Woodard’s 2005 dissertation, “Exploiting Finger Surface as a Biometric Identifier,” became the opening salvo in an ongoing volley of academic papers and book chapters focused on ways to collect and analyze biometric data — everything from eyebrows to “iris segmentation” to “soft,” or behavioral, biometrics.

“I spent a year as a [post-doctoral fellow] at Notre Dame, sponsored by the director of central intelligence,” said Woodard. “Biometrics is what my career has been built on.”

The intelligence community’s initial support came at a critical juncture: Woodard’s family in New Orleans had recently suffered multiple tragedies. In 2003, two years before Woodard made history as Notre Dame’s first Black doctorate in computer engineering, his mother died of a stroke. For various reasons, she had never attended his prior graduation ceremonies, but Woodard had assured her she would be front row for this one. Now that longed-for moment was ripped from their grasp.

“She saw me through the process, but she never saw the ending,” said Woodard with emotion in his voice.

More than anyone, Gwendolyn had believed he would make it as a computer scientist, even when others laughed in his face. He says it isn’t hard for him now to imagine the feisty woman relishing his triumph over the smug naysayers.

“If she were alive right now, my mom would be talking so much trash [to those people]!” he said, chuckling.

Unfortunately, Woodard can only preserve her memory mentally. Hurricane Katrina destroyed his family home and all their photos in August 2005. Three months later, his younger brother Jason was killed. The pain was almost unbearable, he says, but his academic “family” saw him through.

“Some of the worst times of my life were while I was at Notre Dame, but the support system I had there was phenomenal,” remarked Woodard.

Birth of a Mentor

Fortified, Woodard vowed to fulfill a promise he had made to his mother on her deathbed: help his other younger brother, Brian, go to college.

Brian had dropped out of high school when Woodard did, obtained his GED and went into the military. After Katrina hit, Woodard invited Brian to live with him in Indiana and enroll in nursing school.

“Not only did he finish nursing school, he graduated at the top of his class,” Woodard said proudly.

Woodard’s own career took off in 2006 when he joined the faculty of Clemson University’s School of Computing. There he extended his biometric research into keystroke dynamics, gender classification, machine learning and how aging affects people’s susceptibility to online scams, among other areas.

He also earned praise and awards for his effective mentoring of “nontraditional” students –women, minorities, first-generation students and those who start college at age 25 and up.

Woodard’s unique skillset didn’t escape the attention of his department chair, Dr. Juan Gilbert. When UF recruited Gilbert to head its Department of Computer and Information Science and Engineering (CISE) in 2015, Gilbert hand-picked Woodard and four other Clemson computer scientists to relocate with him to Gainesville.

“It was an easy decision to bring Dr. Woodard,” said Gilbert in a recent interview. “Not only is he an outstanding scholar and researcher – his work in biometrics is top-notch – he’s an exceptional person as well. He’s an excellent communicator and works to solve problems when they arise.”

When Woodard bade goodbye to the Clemson Tigers, one of his leading graduate students, Tempestt Neal (PhD ’18), followed him to UF. The daughter of a cosmetologist and a military veteran, Neal went on to make Gator history as the first African American woman to receive a doctorate in computer engineering from CISE.

“I credit much of my success to Dr. Woodard’s mentorship — he’s a game changer!” said Dr. Neal, now a tenure-track professor at the University of South Florida. “He takes on a ‘cool uncle’ approach, where he isn’t a hand-holder, nor is he hands-off. He allows his students to find their own way in nearly every aspect that matters in a PhD program….”

Now that Neal is mentoring her own students, she says she often finds herself wondering, “What would Dr. Woodard say about this situation?”

“He remains available when I text or call,” she added. “He’s a role model, for sure.”

“I credit much of my success to Dr. Woodard’s mentorship — he’s a game changer!”

Dr. Tempestt Neal, first-generation alum, now a tenure track faculty member at the University of South Florida

Valuing “Diversity of Experience”

Married since 2008, Woodard enjoys a quiet life in Gainesville, where, in his rare free time, he enjoys good food and playing video games (first-person shooters are his favorite, his says).

Looking back on his unorthodox career path, he says his bumpy journey only made him stronger and more resilient. He knows the value of grit and emphasizes to students that intellect alone is not enough; persistence and punching back after setbacks are the foundations of success.

Lessons like these can’t be gained by reading academic papers, he says. People have to experience them directly and pass them on to the next generation. He hopes that when hiring faculty members, universities will increasingly value nontraditional applicants who have overcome hardships to become standouts in their field.

“If the entire faculty is made up of people who only followed the strict path [to an academic career], you’re going to get a certain way of thinking,” said Woodard. “But if you mix in those folks with people like me, you get a diversity of experience that makes the whole institution stronger.

“Who better to help people overcome adversity than someone who’s climbed that mountain themselves?”

More About

- Watch this short CISE video to learn about Dr. Woodard’s biometrics research: https://uff.to/j214z9

- Visit Woodard’s UF homepage at www.damonwoodard.com